- Home

- Erica Waters

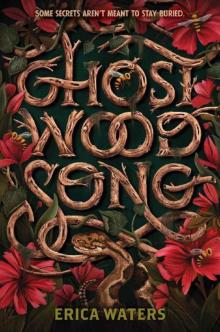

Ghost Wood Song Page 4

Ghost Wood Song Read online

Page 4

When we finish, the crowd applauds loudly, and a few people whistle. Thank God—Sarah was dreading the polite applause some performers get at these open mics. She says it’s worse than being booed.

When she jumps off the stage, she’s still high on the music—smiling wide enough to show the little gap between her front teeth she always tries to hide. She even gives Orlando and me one of her rare hugs, leaving me with the lingering fragrance of vanilla in my nose. “You both were amazing,” she says. “I think we could win this.”

When Cedar and Rose take the stage, the room goes quiet again. Rose’s banjo catches my eye. It’s small and vintage-looking, without a resonator. I bet it’s at least a hundred years old. I glance at Sarah to see her reaction. If the hours she’s dragged me through music stores looking at banjos are any indication, she can probably name that banjo’s year and maker. But she’s only got eyes for Rose, and I can’t tell if her expression is love, hate, or some combination of the two. A stab of jealousy goes through me, but then Cedar and Rose begin playing and I forget about Sarah.

The notes are quick and sharp and bright, the melody cheerful as springtime. Yet as Rose’s fingers dance over the strings, the hairs on my arms stand on end and my whole body goes cold.

They’re playing a song as familiar to me as the rhythm of my breath, the beat of my heart. I think it must be carried along in my bloodstream, singing through every artery and vein.

“Shady Grove,” the song that gave me my name.

They’re playing it fast, the tempo quicker than how Daddy played it, but the heart of the song’s still there. And then Cedar begins to sing, his tenor voice ringing out through the room.

Shady Grove, my little love

Shady Grove, I say

Shady Grove, my little love

I’m bound to go away.

Daddy named me after this song, a hundreds-year-old Appalachian ballad with a thousand variations, though he had Doc Watson’s in mind when he decided to call me Shady Grove. He said he knew that’s who I was the moment I opened my pretty brown eyes and screamed at the world like my heart was breaking. Of course, now everybody calls me Shady, and most people don’t know why.

Daddy sang me to sleep with this song and sometimes he woke me up with it, too. But as the song says, he was bound to go away. Yet here he is again, calling to me, doing everything he can to reach me, even from the grave. What’s he trying to tell me?

Cedar’s voice draws me in, while Rose’s fingers dance over the banjo strings like a spider’s legs, spinning a spell that catches me whole. Wrapped up in their song, I can’t do anything but listen and breathe and try to keep the tears from my eyes.

But they’re already spilling down my cheeks.

Maybe my daddy wants me to know his fiddle’s still out there somewhere, waiting for me to play it. Maybe he’s been listening to me play in the woods the last few weeks and knows I’m ready now. The thought sends a shiver up my spine.

I feel a gentle pressure on my arm. I’m surprised to see Jesse’s beside me, wearing his worried eyes. He must have come to find me because of the song, because he knew I’d need him. A sob is building in my chest, so I lean in to him and bury my face in his shoulder. I’m so grateful my brother came tonight, and that he’s here with me for this. Jesse puts an arm around me and holds me close until the song ends. I wonder if the memory of Daddy’s voice cuts through him as sharp as it does through me.

Most of all, I wonder what this song means, what Daddy’s trying to tell me. Is he reminding me of who I am or warning me about something still to come?

Five

Cedar smiles his cowboy smile and tips his hat, heading off the stage like he didn’t just rip a hole in my chest. Rose follows close behind, not even glancing at the cheering audience.

I give Jesse a hug to thank him and head to the bathroom, pushing my way through the packed, noisy crowd. Someone onstage has started singing “Wagon Wheel,” which ought to make me smug as hell, but all I can think about is putting a bathroom stall door between me and everyone else.

I let myself into the only empty stall and lean against the door with my face in my hands, my mind heaving. It’s only a song, I say to myself. It’s not even uncommon. It’s in every bluegrass player’s repertoire. It’s half a miracle I haven’t heard it played before now.

But my skin is still tingling, pricked with chill bumps that won’t leave.

The fiddle notes finding me in the forest weren’t echoes, and Cedar and Rose’s choice of song wasn’t a coincidence. The music from the pines has carried all the way to Kellyville.

“Shady,” someone says on the other side of the stall door. Sarah. “You all right?”

I open the door after a few seconds and meet her soft brown eyes. We gaze at each other until tears fill my eyes again, and Sarah looks away. Sarah’s mom died when she was a toddler. She hasn’t said it outright, but I think she killed herself. But even though Sarah’s lost a parent too, she always seems embarrassed by my grief.

“Come on, I’ll buy you another coffee,” Sarah says, her voice gruff. “You’re missing all the music.” She reaches out uncertainly and takes my hand to pull me from the stall. Warmth spreads up my arm, and I automatically lace my fingers in hers. She doesn’t let go.

We leave the bathroom together and run straight into my stepdad. Jim looks down at us, surprise turning his dark, angular face slightly comical. Sarah drops my hand. She’s out to her dad and her friends, but she keeps it quiet around other people. And I sure as hell haven’t mentioned being bi to Mama or Jim.

“I didn’t know you were coming,” I say. “Is Mama here?” I didn’t invite them.

Jim nods toward the stage. His son, Kenneth, is up there with a guitar singing “A Boy Named Sue,” by Johnny Cash, and really hamming it up. He’s sweating hard in the overhead lights, his fair skin turning pink from exertion.

“I didn’t know Kenneth played,” I say. “He’s pretty good.”

Jim nods again, like he can’t be bothered to praise his own kid. Kenneth lives with his mama and his stepdad and hardly ever sees Jim, which is fine by me. I can’t imagine having Kenneth hanging around on weekends. I’m just shocked Jim showed up for this, of all things.

Then I catch a glimpse of Jim’s brother, Frank, out of the corner of my eye, making his steady way toward us. He smiles at me and nods at Jim, whose face flushes a deep crimson. Frank looks like Jim, if Jim were about a hundred pounds heavier and sporting a graying beard. His nose looks like it’s been broken at least twice. But Frank’s the good brother, the one who took over their daddy’s business and made it strong, who got married and stayed married, who gave his little brother a job whether he deserved it or not. He’s got plans to run for city council next year, which is making Jim even more bitter toward him than usual.

“I’ll see you at home,” Jim says to me, striding back toward Frank, squeezing his hands into fists at his sides as he goes.

“A real conversationalist,” Sarah mutters. She hurries toward the coffee bar, her hands buried in her pockets.

“Better than Kenneth, who never shuts up,” I say, trying to act normal, like I don’t want to grab Sarah’s hand again and never let go. Like my stepdad’s not making his way toward his older brother with hatred in his eyes. Like I’m not being haunted by my father’s music.

There’s a long line, but we finally get our drinks and head back to Orlando and Jesse, who are cringing at the terrible folk singer who just started. They both look up in relief. Orlando’s been my best friend for three years, but he’s still never learned how to have a conversation with my brother. The only thing they have in common is me.

“You guys were great, but I’m gonna take off,” Jesse says, “if that’s all right.” His voice is gentler than usual, his eyes still worried, expectant.

“Thanks. Did you come with Jim? Do you need a ride?” I ask.

“Shit, Jim’s here?” Jesse says, darting looks at every corner.

“Yeah. So?”

“Frank thought I was stoned today and gave me a twenty-minute lecture. Then he made one of the workers drive me home,” he says, ducking down into his chair. Jesse’s been working for Frank part-time since he turned sixteen. Daddy used to work for the same company a long time ago when he and Jim first became friends, when Jim’s father was still alive and running the company.

“Were you stoned?” I say, crossing my arms over my chest.

Jesse shrugs.

Kenneth bursts through the wall of people, and I can see at a glance that he most definitely is stoned. “Jesse,” he yells, so loud people turn to look.

“Shit,” Jesse says again.

Kenneth is bouncing on the balls of his feet. “Thanks again, man, for . . . well, you know. I don’t think I could have gotten through that without it.”

Sarah, Orlando, and I swivel in one motion to gape at Jesse. “Tell me you didn’t,” I say. “What did you give him? Jim’s going to kill you.”

“My dad’s here?” Kenneth says. He’s talking so loud.

“Shut up, man,” Jesse says. “Keep it down.”

“I bet Uncle Frank guilted him into coming,” Kenneth says. “He’s here somewhere.”

So that explains it. Frank is always nagging Jim about how he’s not a good enough dad to Kenneth. I’m glad Frank made him come this time. No matter how much I dislike my stepbrother, I don’t like to see Jim hurt his feelings.

“No way, Jim told me he was excited to see you play,” I lie. “He said you’re really good.”

But Kenneth’s mind has already jumped to something else. “Shady, you want to dance?” he says, yanking me from my chair. His hand is sweaty and I pull away from him, stumbling into Orlando’s lap.

“Oh, so that’s how it is?” Kenneth says, eyeing Orlando. “Or is it her?” he adds when Sarah glares at him. His eyes are glassy and strange.

I glance at Sarah, and Kenneth’s eyes go ludicrously wide. He lets out a giggle. “Jesus, Shady, are you a lesb—”

Jesse gives Kenneth a warning push before he can finish the question. Jesse barely touched him, but Kenneth is so stoned he stumbles over a chair, falling on his ass.

“Sorry, man,” Jesse says, starting to offer Kenneth a hand back up. “You need to watch how you talk to my sister.” But Kenneth’s already up and swinging like a drunken windmill. He misses Jesse’s face and staggers, off-kilter. Guess he inherited Jim’s temper, or maybe it’s just the drugs.

“You’re out of it. Go home,” Jesse says, pushing Kenneth away again. “Go find your old man.” But Kenneth grabs his arm, and Jesse’s starting to look pissed. I know that look, and I try to step between them, but then Kenneth leans right up in Jesse’s face. He says something I can’t hear over the music and laughs. Jesse’s expression changes from anger to rage as fast as I can blink, and then he grabs Kenneth by the front of his shirt and pushes him backward until Kenneth trips and falls, smacking his head on the concrete floor. Jesse doesn’t care. He drops to one knee and drives his fist into Kenneth’s face.

“Jesse!” I scream, racing to pull him off Kenneth, but he’s strong from all those afternoons and weekends working construction with Jim. He raises his fist again. I pull his other arm as hard as I can, but it’s not doing any good. People are beginning to turn their attention from the musicians onstage to the fight, but no one jumps in to stop it. I’m about to yell for help when someone else steps up beside me and yanks Jesse’s other arm. Together, we manage to haul him off Kenneth, who’s pouring blood from both lip and nose. One eye is already starting to swell closed. But he manages to sit up, so at least he’s not unconscious.

Jesse is twisting and fighting against our hold, trying to get back to Kenneth. I finally manage to glance over to see who’s helping. It’s Cedar Smith, his hat knocked off, sweat gleaming at his forehead with the effort of holding Jesse back.

Jesse twists out of our grasp and lunges for Kenneth again, but Jim’s long, wiry arm snatches him out of the air. Jim gets ahold of him by the waist and drags him toward the front door with an iron grip. Jesse fights back, but it doesn’t do any good.

“Make sure Kenneth’s all right,” I tell Cedar and sprint off after Jim and Jesse, the sounds of the open mic fading behind me. I need to make sure they don’t start fighting too. One more blowup and Jesse’s going to get kicked out of our home. I can’t let that happen.

By the time I reach them, they’re almost to Jim’s truck. Jesse finally wrenches himself from Jim’s grip. He starts to say something to Jim, but Jim slaps him flat-handed across the face.

Jesse’s eyes clear and then turn cold and hard as two marbles.

I push past Jim and put myself between them before worse can happen. “Don’t hit my brother again,” I yell at Jim. Then I turn to Jesse. “What the hell is going on with you?” I ask. “Why did you do that?”

“You two get in the goddamned truck,” Jim says. “I’m going to get Kenneth.”

Jesse gives me a long, angry look and then sets off across the parking lot without a word, disappearing around the side of the building. I wait until Jim and Cedar come out, supporting Kenneth between them. Frank trails behind them, his arms crossed, a look of concern on his face. “You want me to call Gary Jones?” Frank asks. Gary is Kenneth’s stepdad and a local cop, not to mention Frank’s friend. Probably the last person Jim wants to see now, excepting Frank himself.

Jim ignores him and turns his scowl on me. “I told you to get in the truck.”

“Jesse took off.”

Jim swears.

“Your friend asked me to give you your fiddle,” Cedar says, handing over my case. He offers me a sympathetic half smile.

God, what absolute trailer trash we must seem like right now. “Thank you. And thanks for helping, but I’m not leaving.” I turn to Jim. “I’m getting a ride home with Orlando. I want to stay and see who wins.” Sarah will be so pissed at me if I bail now, and I definitely don’t want to spend my night at the hospital.

But Frank is still watching us like a hawk, and Jim is past caring what I want. “Shady, I swear to God if you don’t get into this truck right now—” he growls. He can’t stand for anyone to disagree with him in public, and with Frank standing by, he’s even more on edge. His tone says I’ll end up grounded if I don’t go.

The night’s already ruined, so I climb into the tiny back seat of the truck, and Cedar helps Jim hoist Kenneth into the front seat. He talks to Jim for a minute and then waves at me through the truck window.

Jim gets in and slams the door. “What in God’s name was that all about?” he asks once we pull out of the parking lot.

Kenneth gives a broken laugh and then winces. “I was running my mouth like you always told me not to,” he says. That’s Kenneth’s one redeeming quality—he’s an asshole, but at least he owns up to it.

“I figured as much,” Jim says. “He shouldn’t have beat you like that though.”

“What’d you say to him to make him go after you?” I ask, leaning around Kenneth’s seat. “He wasn’t really trying to hurt you at first.”

Kenneth looks away, out the window, watching the fast food joints fly by. “I . . . I don’t remember.”

Jim snorts. “Is that your shame talking, or you got a concussion?”

The hospital is only half a mile away from the café, so we’re pulling up to the emergency room entrance before Kenneth can decide how to answer.

“Shady, go get this fool boy a wheelchair,” Jim says.

I hop out and run inside, and when I come back out with the wheelchair, Jim’s standing on the pavement, leaning into Kenneth’s door, holding a balled-up cloth against his son’s bleeding face. That’s the most I’ve ever seen Jim act like a father to Kenneth. Still doesn’t make up for years of being a shitty dad though.

Kenneth is taken straight back to the emergency room by a nurse, and Jim leaves to park the truck. The waiting room is nearly empty, so I get a chair by the wall and watch the muted TV over

head. I text Sarah. Sorry I had to go. Jim’s being a dick. Did we win???

Ten minutes go by and I’m starting to think she’s decided my family drama isn’t worth her time. But then my phone dings. They just announced. Some basic-ass country pop singer won. Judges were tasteless idiots. She follows it up with a rolling-eyes emoji.

Sorry, I type back. I am, too. I didn’t really care about the open mic like Sarah did, but after how good it felt to play up there, losing stings a little bit. And I can’t help but wonder if some part of Sarah blames me.

I’m surprised Cedar and Rose didn’t win. They were incredible—even apart from the song they chose. I realize I would love to play with them sometime, might even like to be a part of their band. But even thinking about playing with someone besides Sarah and Orlando makes me feel guilty.

As if she can hear my disloyal thoughts, Sarah doesn’t respond to my text, so I put my phone away and watch the local news. Before long, I start to drowse. The stresses of performing, hearing Cedar and Rose play “Shady Grove,” and then this nonsense with Jesse . . . After a week of chasing echoes, I’m so tired, worn down to just about nothing.

I’m awake and then I’m not, the sterile hospital atmosphere merging horribly with whatever my imagination is dreaming up. I’m on a stretcher in a dark room, lying on my back and peering up into the darkness, which seems to go on forever, like I’m at the bottom of a well.

But then the darkness starts to move, swirling around me like black smoke. It touches me with the clammy dampness of a frog’s skin, making my whole body turn to goose bumps.

I lean away from it, but the stretcher has disappeared, along with the room. A sharp, shrill sound like music from an out-of-tune fiddle begins to play. I try to cry out, but the darkness fills my mouth, stopping up my throat.

I writhe and struggle in its grasp, but I’m bound and gagged and growing more panicked every second. I can’t tell the difference between the horrible darkness and the horrible music anymore—they’ve morphed into a single, inescapable monster.

Ghost Wood Song

Ghost Wood Song